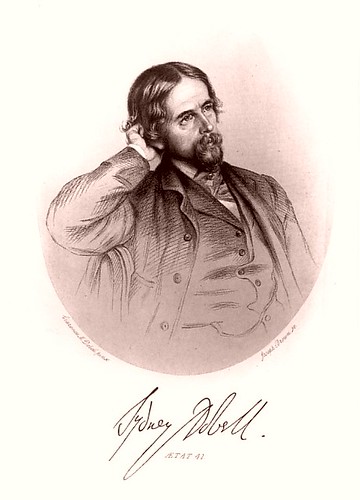

Sydney Dobell—"Farewell"

(England in Time of War, 1856)

Can I see thee stand

On the looming land?

Dost thou wave with thy white hand

Farewell, farewell?

I could think that thou art near,

Thy sweet voice is in mine ear,

Farewell, farewell!

While I listen, all things seem

Singing in a singing dream,

Farewell, farewell!

Echoing in an echoing dream,

Farewell, farewell!

Yon boat upon the sea,

It floats 'twixt thee and me,

I see the boatman listless lie;

He cannot hear the cry

That in mine ears doth ring

Farewell, farewell!

Doth it pass him o'er and o'er,

Heard upon the shore behind,

Farewell, farewell!

Heard upon the ship before,

Farewell, farewell!

Like an arrow that can dart

Viewless thro' the viewless wind,

Plain on the quivering string,

And plain in the victim's heart?

Are there voices in the sky,

Farewell, farewell?

Am I mocked by the bright air,

Farewell, farewell?

The empty air that everywhere

Silvers back the sung reply,

Farewell, farewell!

While to and fro the tremulous accents fly,

Farewell, farewell!

Now shown, now shy,

Farewell, farewell!

Now song, now sigh,

Farewell, farewell!

Toy with the grasping heart that deems them nigh,

Come like blown bells in sudden wind and high,

Or far on furthest verge in lingering echoes die,

Farewell, farewell!

Farewell, farewell, farewell!

Oh, Love! what strange dumb Fate

Hath broken into voice to see us hope?

Surely we part to meet again?

Like one struck blind, I grope

In vain, in vain;

I cannot hold a single sense to tell

The meaning of this melancholy bell,

Farewell, farewell!

I touch them with my thought, and small and great

They join the swaying swell,

Farewell, farewell!

Farewell, farewell, farewell!

Aye, when I felt thee falling

On this heaving breast—

Aye, when I felt thee prest

Nearer, nearer, nearer,

Dearer, dearer, dearer—

Aye, while I saw thy face,

In that long last embrace,

The first, the last, the best—

Aye, while I held thee heart to heart,

My soul had pushed off from the shore,

And we were far apart;

I heard her calling, calling,

From the sea of nevermore

Farewell, farewell!

Fainter, fainter, like a bell

Rung from some receding ship,

Farewell, farewell!

The far and further knell

Did hardly reach my lip,

Farewell, farewell!

Farewell, farewell, farewell!

Away, you omens vain!

Away, away!

What! will you not be driven?

My heart is trembling in your augury.

Hence! Like a flight of seabirds at a gun,

A thousand ways they scatter back to Heaven,

Wheel lessening out of sight, and swoop again as one!

Farewell, farewell!

Farewell, farewell, farewell!

Oh, Love! what fatal spell

Is winding winding round me to this singin?

What hands unseen are flinging

The tightening mesh that I can feel too well?

What viewless wings are winging

The syren music of this passing bell?

Farewell, farewell!

Farewell, farewell, farewell!

Arouse my heart! arouse!

This is the sea: I strike these wooden walls:

The sailors come and go at my command:

I lift this cable with my hand:

I loose it and it falls:

Arouse! she is not lost,

Thou art not plighted to a moonlight ghost,

But to a living spouse.

Arouse! we only part to meet again!

Oh thou moody main,

Are thy mermaid cells a-ringing?

Are thy mermaid sisters singing?

The saddest shell of every cell

Ringing still, and ringing

Farewell, farewell!

To the sinking sighing singing

To the floating flying singing,

To the deepening dying singing,

In the swell,

Farewell, farewell!

And the failing wailing ringing,

The reaming dreaming ringing

Of fainter shell in deeper cell,

To the sunken sunken singing,

Farewell, farewell!

Farewell, farewell!

Farewell, farewell, farewell!